In this interview, Melanie Ehren (LEARN! ) talks with Thomas Hatch about how the Dutch education system responded to the COVID-19 pandemic and what has happened since. This interview is part of a series by the International Education News, exploring what can change in schools after the pandemic.

Interview highlights:

Thomas Hatch (TH): Can you give us an overview what happened in schools in the Netherlands after the COVID-19 outbreak? When did schools close and how long were they closed?

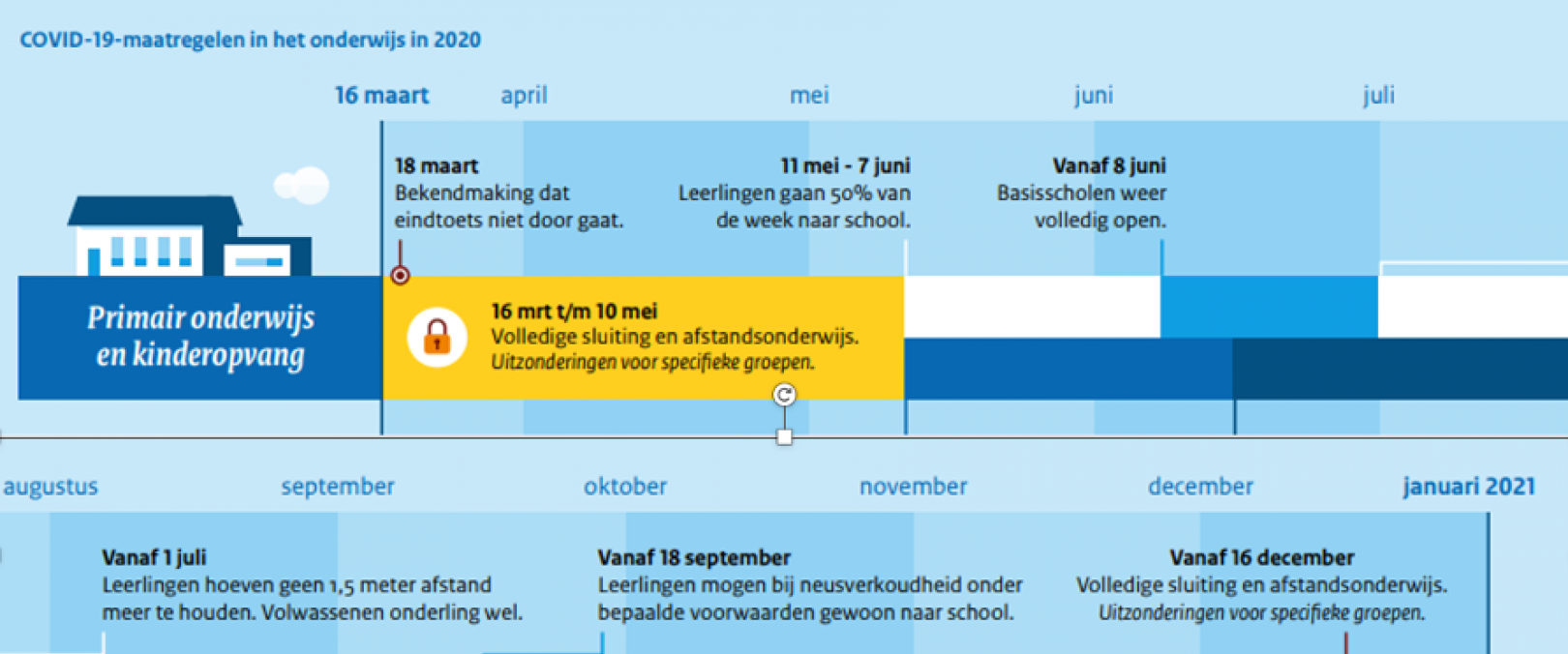

Melanie Ehren (ME): The national government closed schools three times. The first national closure lasted from March 16 to 10 May 2020 (for primary schools) and until the 2nd of June (for secondary schools). Teaching and learning was fully online during that time. The second national closure went from the 16th of December 2020 until the 8th of February 2021 and then the third national closure went from 14 December 2021 until 10 January 2022, although this was more of an extended Christmas break. All the closures were in response to a rise in cases, but around the time of the second closure there was also a discussion about whether closing schools was the best measure to prevent virus spread. The argument for closing schools included that it would help enforce the working from home policy. Too many people were still going into work and by closing schools, parents had to stay home with their children.

When schools reopened after the first and second closures, schools had to ensure social distancing of 1.5 metres between people inside and ensure good hygiene. Schools were allowed to decide on how to meet these guidelines, with support and proposed models by the national councils for primary and secondary education. In response, schools did things like splitting classes in half with some students attending during the first part of the week and the rest attending at the end of the week. Even though the periods of national school closure were relatively short in comparison to some other countries, the disruption lasted much longer. For example, even when schools were technically open, many teachers and classes had to quarantine for periods of time. Since the beginning of the school closures, the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture, & Science has monitored the reduction in lesson hours due to COVID over the pandemic in a series of monthly reports. The Dutch Inspectorate of Education also documented the timeline of COVID-related decisions in 2020 (including the start of the second closure in December of 2021) and then again in 2021 in their annual reports on the state of education.

March 2020 – January 2021

Timeline of school closures and related decisions for primary schools (closures = yellow)

The State of Education 2021, Dutch Inspectorate of Education

TH: What was the initial response from policymakers and others in terms of support?

ME: In the Netherlands, there was a coordinated approach by the national councils for primary and secondary education, the ministries for education and economic affairs and a national association of school boards. That approach focused on ensuring that all students had access to online learning when schools were closed. These organisations collectively investigated how many students and teachers did not have internet connections or laptops at home. Based on this information, telecom providers searched for the best solutions together with the parties involved. Those solutions included issuing hotspots and creating public Wi-Fi networks and arranging laptops for children who needed them. In addition, NPO Z@ppelin, a national broadcaster, initially offered instruction on television for children without a laptop/tablet. But I also saw schools where teachers would just hop on their bicycle and tour around the city to check in with families and have conversations on the doorstep.

A lot was left up to the initiative of the boards of each school and the networks responsible for ensuring inclusive education in each region. Honestly, because the Dutch school system is so decentralized, we just don’t know what happened at the school level in a lot of communities. All this raises a really interesting question: are highly centralized systems or more decentralized systems are best equipped to deal with a crisis like the pandemic? To me, the examples of teachers going door to door to check in with kids really speaks to teacher agency and how teachers understand their role and responsibility. That agency is a really important thing to have during a pandemic, but also when thinking about school quality in general. My colleagues and I wrote about some of these issues of teacher agency from the perspective of several different education systems (Teaching in the COVID-19 Era: Understanding the Opportunities and Barriers for Teacher Agency).